SCE to AUX

DevOps lessons from a disaster averted

50 years ago today, the Apollo 12 mission was saved by a scrappy young engineer who, when confronted with an unknown situation, quickly assessed what was going on and made the now famous call: “Flight, EECOM, try SCE to Aux.”

In the history of the US Space program, it’s somewhat of a footnote, known and understood by only a handful of geeks with engineering backgrounds. The drama was brief and far less public than the Apollo 13 crisis of several months later, the first moon lander just a few months prior, or the dramatic Christmas-eve reading of the Bible from lunar orbit during Apollo 8. But for us geeks and engineers the events that took place during the first two minutes of the Apollo 12 mission have a special place in the pantheon of engineering successes. Maybe it’s because the hero is himself an uber-geek, John Aaron, in his square black glasses and a headset. Maybe it’s because the situation itself is so familiar: a crisis with a short time frame for resolution and a quick engineering solution that addressed it perfectly. And maybe it’s because it is pretty obscure and seems like “not a big deal” unless you really try to understand what happened.

What happened?

I won’t get into the details here, as they’re well-documented. Apollo 12 launched in the rain and was struck by lightning twice. The first knocked the fuel cells to the command module offline causing every warning light to go off. The second knocked them all out completely. On the ground, Aron saw the pattern on his screen and recognized it from a simulation he had observed (but not participated in). He made the call that would bring the instruments back to life and by doing so allow the crew to quickly and easily diagnose and fix the problem.

I’m a DevOps engineer, not an astronaut!

So what does this have to do with DevOps? Plenty as it turns out. Assuming you’re willing to think and learn, and if you’re not maybe DevOps isn’t the right job for you. [Just being honest here. If you never want to think out of the box, you’re in the wrong profession.]

Do your game days: Drill, drill, and drill some more

Eisenhower famously noted that battle plans are useless, but battle planning is indispensable. What he meant by this is that no battle (or any other complex event involving multiple independent actors) will ever go as planned. But a proper planning exercise will require options to be considered, ideas to be floated, simulations to be run, studies to be made, and a greater understanding to be developed. All of this is indispensable when the first shot is fired and everybody in the chain of command has to consider how to react to the new reality. Planning ultimately gives you options to work with when the unexpected happens, which is will.

Apollo 12’s situation was never simulated. It was never even considered. Mission Commander Pete Conrad later joked that “I think we need to do more all-weather testing.” A lightning strike, let alone two of them less than 20 seconds apart were not ever part of the drill.

However, over the course of the Apollo program, enough simulations were done that the symptoms of the Apollo 12 event had been duplicated, and that was enough. It did not matter that the simulation had been for a completely different event (unexpected power drop), the fact that they generated a certain pattern of gibberish on the EECOM’s screen was enough information to drive the “SCE to AUX” call.

Game days are not jokes, or wastes of time unless you treat them as one, in which case you’ll never learn from them.

Be curious and dive deep

The two people who made the solution work were both relatively new. Lunar Module Pilot Alan Bean had been added to the Apollo crew rotation after Clifton Williams was killed in a crash. He had missed an opportunity on Gemini and almost missed Apollo as well. He was brought on by Conrad, who had previously been his instructor, saw his talent and personally requested him. He threw himself into the new job and caught up with, and some would say exceeded the abilities of those who had been there longer.

Aaron was known for his curiosity. He was not a participant in the sim that revealed how problems with the Signal Conditioning Equipment (SCE) would reveal themselves. He chose to observe and learn. When he saw something he didn’t understand, he asked about it. He spent time with the engineers from North American Aerospace who explained to him how the SCE worked and why it failed in that way.

Listen to your juniors

John Aaron was 24 years old. Bean was the newest astronaut on the crew, in fact one of the newest in the program. As noted previously, he was added late after another astronaut was killed.

One of the things Apollo did really well was giving people jobs and then expecting and trusting them to do those jobs. When Aaron called out “SCE to AUX,” flight director Gerry Griffin (himself new in that role) did not second guess him or wait for another opinion. Sure he was junior, but he had the training to do the job, and at that moment with only seconds left to make the right call, he was doing his job. Griffin’s response was “what the hell is that?” because he didn’t remember and possibly didn’t even know what “SCE” was, but he didn’t let that stop him from having the command relayed to the spacecraft.

And if you need to go with a seasoned person’s advice over that of a junior person, there are always much better ways of making the call without resorting to “Shut up Wesley.” If there aren’t, is your decision really defensible?

Don’t do anything just to do something

Don’t do nothing if there’s anything you can do

Alan Bean later remarked that in the Apollo capsule the practice was not to touch the electrical systems without a really good reason. Even with the ship effectively disabled and a looming abort requirement, they avoided touching anything until such a time as they had a good reason to believe that the action would have a good chance of correcting the problem.

Waiting paid off.

But Bean also later commented that had the deadline gotten closer, had no better solution come from mission control, they would have tried alternatives. They would have judiciously started throwing switches. Quite possibly they might have found their way to resetting the power cells, though they likely would not have come up with the SCE option, that nobody but Bean even could remember existing. It would have been a last resort, an effort to try something before the otherwise inevitable abort.

These two opposite guidelines balance against each other, and have to be informed by the situation. How much longer to go? Is there any progress on a real solution? How much damage could be done by attempting solutions at random? Will you make things worse? Will you accelerate the point of no return? Might you be able to delay while a permanent solution is found?

We do this in DevOps as well. In planning for a recent event we discussed what we might do if we were in an impact situation with no obvious solution. What levers might we pull? What nonessential capabilities might we turn off? What changes or resets might we perform that might resolve things even without information?

Obviously, none of these are things we would do lightly. But in an impact situation with no other obvious alternative solution, the question quickly changes from “how do I prevent/fix this?” to “what can I try that won’t make things worse and might help?”

Don’t let one possible solution stop evaluation of others

Listening to the various recorded conversation loops I’m struck by how many people both in the capsule and on the ground are offering ideas and suggestions, right up to the point where one proposed solution is confirmed to have worked.

There wasn’t a lot of time and there weren’t a lot of people who could be brought into the discussion, but in addition to Aron, everybody in the capsule was evaluating and thinking, as were all the other specialists at mission control. Nobody knew whether “SCE to AUX” was going to work until it was tried. And up to that point, continuing to explore all options remained essential. There might have been a different problem and a different solution, or no solution at all. You don’t stop talking about options until you know one has worked.

Find clues in whatever you have

The readings that appeared on John Aaron’s screen were gibberish. They conveyed no useful information the first time he saw them in the sim many months before. But the pattern itself became useful in diagnosis. It was still gibberish, but it was familiar gibberish. It was a pattern that had been seen before.

Patterns can exist in anything. Getting an interrupt or event every 17 seconds? Have you ever seen something else, even something different, that occurred every 17 seconds? That alone might be a clue. How an incident impacts different software or hardware systems might be a clue. Clues are everywhere. One of the benefits of game days is they allow you to build a catalog of different patterns and clues, if you’re paying attention.

I recall an event a while back where a process was terminating unpredictably. We could tell that the memory used by the process was increasing steadily prior to the event, but the process had plenty of memory available. It wasn’t until somebody noticed that the difference in memory use between when the process started, and when it terminated, was always 4.2GB. If you’ve been around for any amount of time, you will recognize the importance of anything where the problem is 2.1 billion (More accurately 2,147,483,647 or 11111111111111111111111111111112). Information was stored in an array, and the index for an array is a standard 32 bit int. Try to go beyond that and things will stop working. That’s not a pattern I was taught in school, but if you pay attention, you’ll see it a lot. In that case, the person who first noticed it was, again, one of our strong juniors.

[The immediate solution was to run the process more frequently so we weren’t accumulating so much data before passing it to the next process. The longer term solution was to choose a more appropriate data structure.]

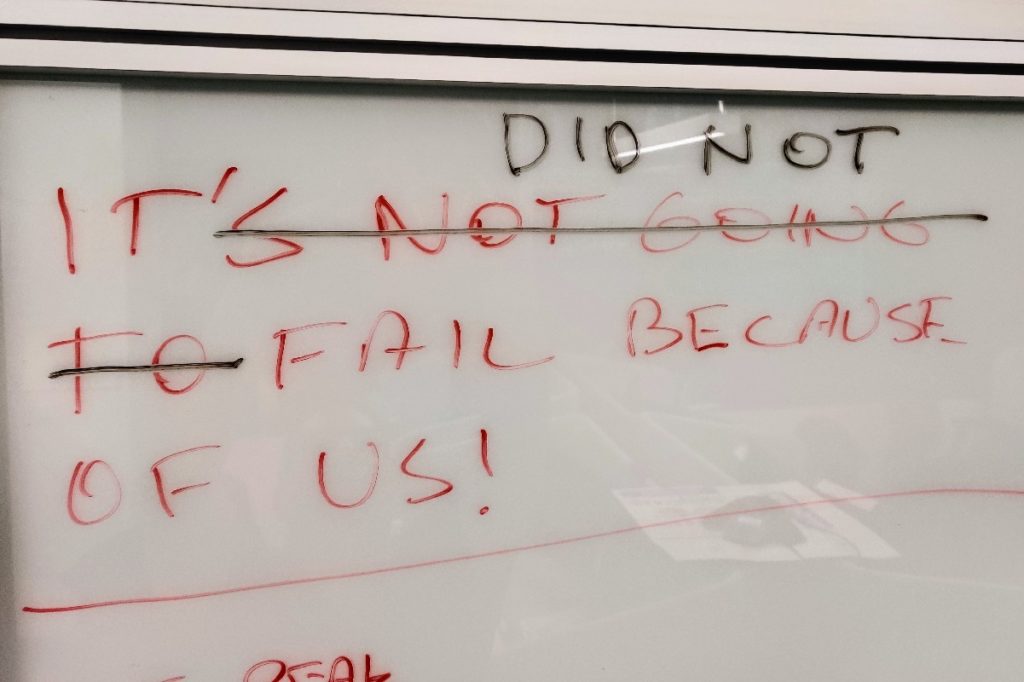

Extra: It’s not going to fail because of me.

Many years after the missions, astronaut Ken Mattingly (Apollo 16) said of the missions that the attitude was, and had to be that “We’re going to make it work. And I don’t know how to make it work. I don’t know how to do… most of this mission. But I do know that I can assure you that my piece of it is going to work. And you won’t fail because of me.”

Mattingly flew on Apollo 16 because he had been displaced from the Apollo 13 crew due to exposure to German Measles in the weeks ahead of the mission. Instead he became the primary person tasked with figuring out how to power up the Apollo 13 command module ahead of re-entry and splashdown, and in doing so helped save the mission and his original crew-mates. When displaced from his original role, he found a new one where his expertise and experience made a difference, and where he could continue to ensure that it would not fail because of him, or even because of some expertise that he might bring to the table that would not be there without him.

In DevOps we wear lots of hats and often have to switch roles. Remembering that wherever you are and whatever you’re doing, “it’s not going to fail because of me” is what the job is about.