A little Linux box

When I left Seattle, one of the things I had to do was reduce my equipment footprint. My old Linux computer — an ancient workstation I had reworked and installed Ubuntu on — was one of the obvious things to get rid of. I considered turning my Windows machine into a dual-boot, but decided against it. I’ve had too many hassles with dual-boot systems over the years, and I doubt Windows has become any more tolerant. I’d love to get rid of Windows altogether, but certain applications just don’t have great alternatives on Linux and they are some of the ones that most require a powerful machine. So the Windows box gained an extra SSD from piecing apart the Linux machine, and the Linux machine was mostly trashed, given how little value there was in most of the components.

Which begged the question of what to replace it with. I used a Raspberry Pi 5 for a while. It was… OK. I mostly used it in terminal mode, and mostly for relatively minor tasks. The more recent generations of Pis are pretty good at that. But even for basic internet activity, a Pi 5 can be painfully slow at times, mostly due to the slow speed of the default Micro-SD card storage. A PCIe adapter and SSD (and an appropriate case, cooler, etc.) can improve the Pi’s performance, but once you’ve added all the necessary pieces, you’re paying as much as a complete PC. I decided not to go there.

I found the Beelink EQ13, a nice little mini-computer with 16MB of RAM, 512GB of SSD storage and a low-power Intel N100 processor, packaged with a low-noise fan and internal power supply that negates the need for an external brick. This specific model is no longer available, which explains the great pricing I got on the previous one, but the current N150-powered EQ14 is substantially similar. Multiple online reviews suggest that there’s no significant performance difference.

The box

There is a lot of video out there, mostly of the refreshed EQ14, including some that address using Linux. I’ll highlight things that matter most to me, as these highlight some of the downsides as well as one big opportunity for improvement. Most reviews spend a lot of time on game performance, that I don’t much care about.

The Beelink is compact, but slightly larger than the old Intel NUC that I use as a media player connected to my TV. The latter uses a fairly hefty external power supply while the Beelink connects directly to AC with the power supply inside.

The interfaces on the Beelink are comparable to other small PCs I’ve used. Looking at it side-by-side with the older NUC, the ASUS loses a Thunderbolt port, adds one more USB3 and a USB2, and doubles up the HDMI and network ports. Networks are still 1GbE, but can be used together for up to 2Gb, if your router/switch can support this arrangement. That makes for a nice little home server.

The inside

Internally, there’s one bank of 16GB of DDR4 RAM. That’s the limit on this family of low-power processors. The newer N150 generation that is now available can support DDR5, but Beelink (wisely, in my opinion) decided not to substantially change the existing design at this time. Benchmarks I’ve seen show at best a 10% improvement from the faster memory, and probably less in real-world use. This is a low-cost and low-power CPU and there’s only so much you’ll get. I won’t be surprised to see a redesign around DDR5 when the N250 and N350/355 become available.

There are two NVMe slots. The CPU can only support PCIe 3 for the two SSDs. The primary slot can support PCIe 3×4 or mSATA, and the secondary one can only handle PCIe 3×1. One reviewer placed a PCIe 4×4 drive into the second slot and complained about the throughput, after previously discarding the documentation unread, and presumably not reading the specs either. It’s important not to ignore the specs on these low-powereed computers, where the limitations are far more likely to be an issue, and a minor difference between two generally similar models can make a very big difference depending on your use case.

Beelink’s choice to use a 512GB mSATA SSD rather than a previous-generation PCIe SSD is disappointing, and the choice is buried on their website. You would need to scroll about halfway down the product page, to find the fine print noting that “(The retail unit ships with a SATA III SSD)“, as that is the only place it is stated. Reading the specs, you would only see “Dual M.2 2280 PCle3.0 SSD Slots, Max 4TB, Options: 500GB.” The actual equipment included should have been made more obvious.

As an aside, I wish I had access to a barebones (“non-retail“) unit so I could choose the size/type for myself.

The cost difference between the SATA storage and a PCIe 3×4 drive is somewhere between “small” and “nonexistent,” so it’s particularly annoying. I replaced it with one from my collection once I realized what was going on, and while I didn’t measure performance, I could appreciate the improvement in startup, software launch and other storage-intensive tasks.

The two SSD slots are covered by a nice heat sink. Beelink includes small thermal pads that only cover the controller and power chips, assuming they are placed correctly. I replaced theirs with a full-length pad.

The wifi card is in its own M.2 slot underneath the primary PCIe. The clearance is very tight and a two-sided SSD did not fit. Fortunately, I have plenty of 250-500GB SSDs lying around so I switched to a single-sided model that fit with no interference. A better design would have swapped the SSD locations, eliminating conflicts for the large majority of people who will never use the second, much slower, SSD slot.

The included wifi card is a low-end intel AX101. While Wifi6 capable, it’s a 1×1 card so may have issues in locations with spotty coverage. It should be easy enough to replace if necessary, but that would further negate the cost benefits of this small device. It was not an issue in my use.

The use of an internal power supply makes the package a bit larger, but easier to deal with than smaller mini PCs that have an external brick. That was a selling point given the number of bricks and wall-warts I already have. It will make it less serviceable in case of power supply failure, but given the cost of the device, I’m OK with that. The power supply sits neatly in on the side of the case.

Installing Linux

Installing Linux Mint was painless. I tried it on both the originally SSD and then on the PCIe replacement, which allowed me some limited impression of the increase in performance. It wasn’t a big deal and I didn’t run benchmarks, but it was noticeable at startup and when launching software.

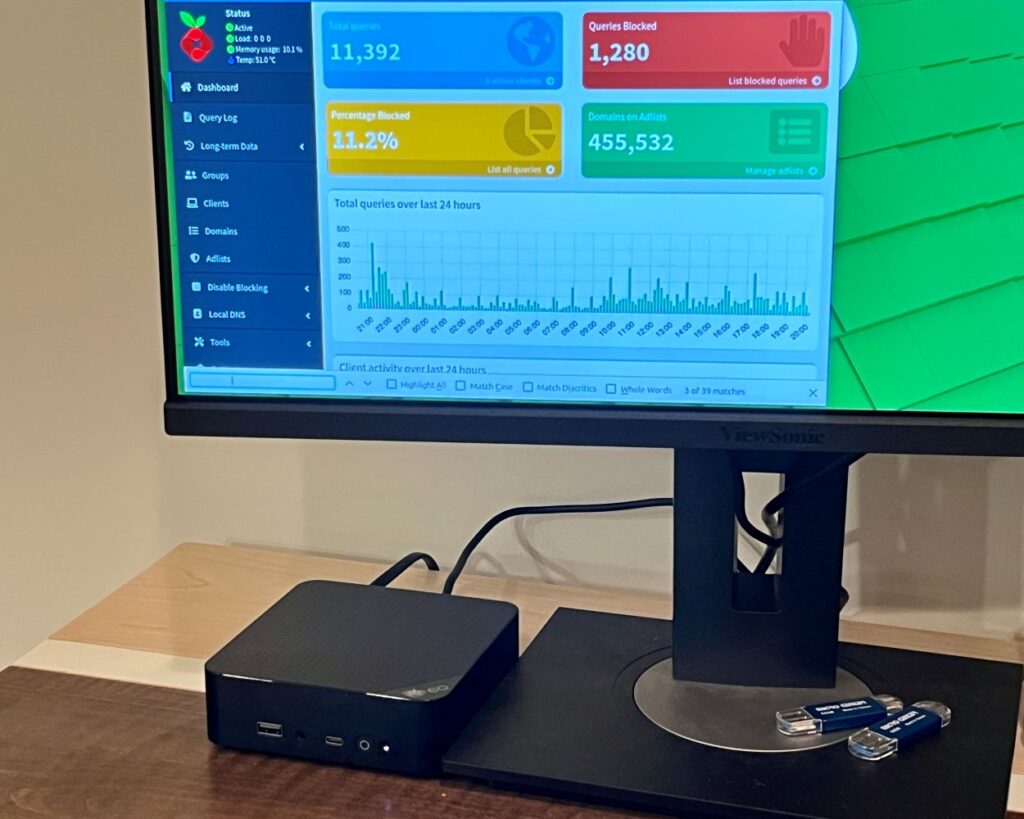

Everything else was as expected. I created an ssh keypair and easily copied the key to the two Raspberry Pis I have running pihole, then to the devices in my Pi cluster. I got emacs installed. The fan is inaudible in normal use, and temps for the CPU, SSD and Wifi card all remain around 50°C except during a CPU stress test, when it got as high as 74°C. Even at that temp, the fan was barely perceptible. I have tested video at standard HD and 2K (don’t currently have a 4K monitor available) and found no consistent difference in temperatures. It’s currently running with a standard HD monitor.

Use

It was find for internet and some basic software use: LibreOffice ran fine for normal use. I can have half a dozen terminal sessions open and ssh’d into various devices with no issue. Even Zoom was fine for all use cases except background replacement. The docs for the Zoom Linux app claim that a quad-core CPU with modern graphics capability is the minimums requirement. The N100 does meet those criteria, but Zoom still does not support those features. If that kind of thing is necessary, I’d pay $30 more for the similar EQi12 (or later “EQi” variants) that come with i3-i7 CPUs and 24GB of RAM.

But my use is light. If I need to run a heavy Linux workload, I tend to just spin up an appropriately size AWS EC2 instance and run it there, which is why I have so many ssh terminals.

Overall

It’s a nice little box that is useful for my limited Linux use case. It would also be quite nice as a small home server and the ability to have two internal SSDs (even if the second is fairly slow) and multiple USB 3.2 external devices opens up a lot of options for somebody using it that way. It would probably be fine as a media server or just as a media playing device hooked up directly to a TV, as I am currently using my older NUC.