Lessons from the top of a snowy hill

It’s snowed in Seattle. Quite a bit of snow in fact.

Seattle doesn’t deal well with snow. Or, for that matter, fallen leaves and general street cleaning which just makes the snow worse when it does fall.

Things are rather treacherous out there. In my neighborhood, we have new-fallen (unplowed) snow, on top of wet (now frozen) fallen, partly-decayed, slippery leaves that were never swept or cleaned up because nobody seems to deal with those here either. The best you have in my neighborhood is the occasional apartment building with a bit a road-salt near the entrance, so things are a mess and we’re all stuck inside.

I’ve been watching the occasional car go by and this has reinforced my desire to stay in. With experience plus AWD and good tires I could handle the conditions, but the other drivers obviously can’t.

Which brings an interesting story. The statute of limitations for minor driving violations in Connecticut is long passed, and dad is no longer around to hear about it, so I guess I can tell this one now.

I learned to drive living on top of a hill. Not just any hill, but a cul-de-sac with only four houses at the end of a long uphill. [Yes, I am New Yorker/Tel-Avivi by birth and birthright, but I did spend the last two years of high school in American suburbia, an experience I’ve chosen never to repeat.] With so few houses, we were the lowest priority road for snow clearing after a storm. It was a very well-off town, but even there it took a day or two after a major storm so you sometimes had to get creative.

I was driving either an ancient rear-wheel-drive Datsun or an even-more-ancient Dodge that had belonged to my grandmother until she had a Driving Miss Daisy incident involving the car, a dropoff at the edge of the road, and a large boulder, that resulted in a bent frame and permanent bad handling. (Dad thought it was a great car for a teenager because it shook uncontrollably over about 45mph and that made for a built-in speed limiter.)

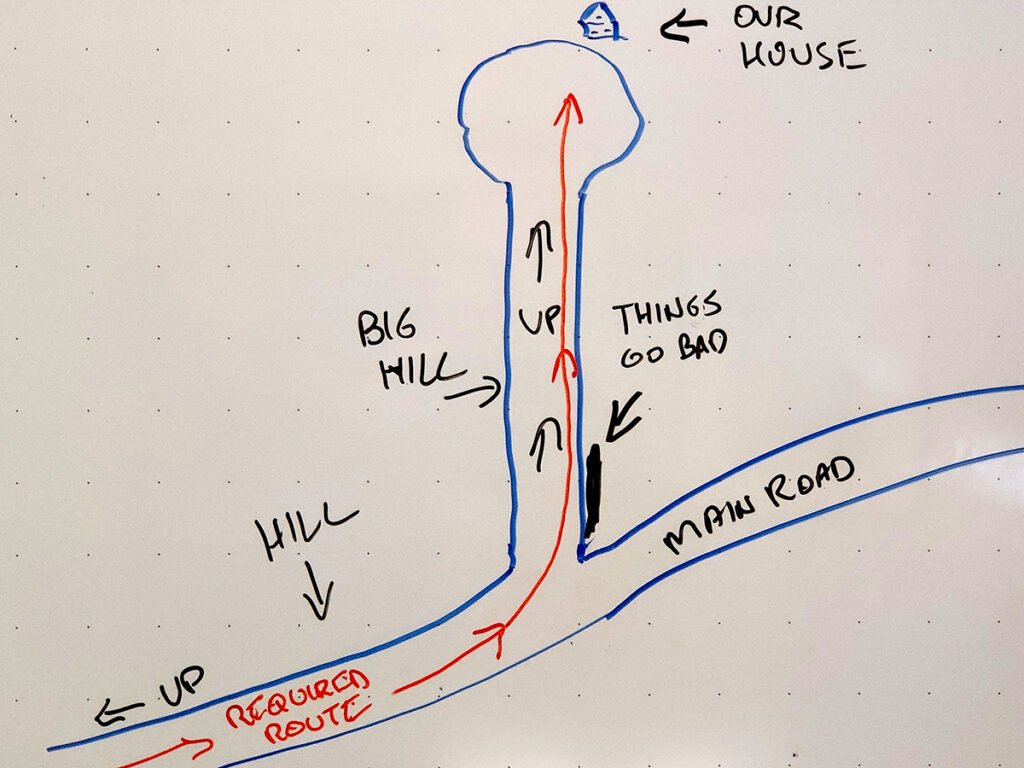

Our hill intersected with a main road that was also a bit of a hill, though not as steep. The road ours intersected with made a bit of a sweeping curve near where the intersection was. It looked kind of like this:

There were two options if the road was slick:

- Park somewhere near the bottom and hope nobody else crashed into your car and/or that you didn’t get plowed in.

- Carry some speed, make the turn, slowly pour on power, and manage to get to the top before you completely ran out of traction.

To teenage me, the first option was not reasonable.

So you had to carry speed. The only way to do this was to drive downhill on the main road that was usually plowed, make a wide turn onto our hill, then add on power as you came out of the turn onto the slick uphill.

Misjudge it and you could end up hitting the curb/upsloping terrain on the far side of the turn. If you ended up a bit sideways, the impact with the curb could pop your tire off the rim. (Fortunately, cars had full-sized spares back then, so you could switch things around, get it fixed later, and hopefully not be noticed. Ask me how I know.)

You had to hit things just right. There was always the risk of opposing traffic on the main road and occasionally a car coming down our hill. There also might be a bit of a berm left by the snowplows on the main road to cross. None of this could be seen until the last seconds, so you had to be prepared to abort and go straight on the main road. I always thought of “go straight” as the default option, with “make a sweeping turn a the last moment” as an option to take only if/when it was available.

But, years later I realize I learned a lot from that kind of driving:

Abort is the Default

This one is always coming up. When I learned to fly my instructor pounded in to me that an aborted landing was the default to prepare for, and that you don’t stop thinking about the abort until you’re on the ground and slowed to the point where you could safely turn off the runway.

At work, I was reminded yesterday that my employer’s stated position is that you should “roll back liberally.” The point being that the default, if anything were to go wrong, or even be suspected of going wrong, is to return to status quo. If you’re driving straight on a plowed road and you suspect something might be inhibiting your ability to safely make a sweeping left turn across traffic onto a slick uphill, you just keep going straight. You can always come back and try again. Same with software deployments.

Adjust to the conditions

The weather where I was could change in an hour. This would change whether/how I handled that curve. I’ve often gotten stuck in an existing plan rather than adjusting on the fly as needed. (By “on the fly” I don’t mean, “without planning.” I mean, “in accordance with changes in underlying conditions, quickly, and in a manner that will minimize impact.”)

This requires that you think through what the alternatives might be in advance. It’s not planning in the way that PMI and others have traditionally taught it, rather it’s planning for the unforeseeable, and understanding how you’ll react to changes in advance, so you don’t have to go through a lengthy review of alternatives when things change. My real-world planning has become much, much better even since I’ve forgotten what PMI taught me, and re-learned the lessons of my youth.

Small changes

There were three things you might have done while trying to get up our hill that would guarantee you a very bad day:

- Stomp on the accelerator.

- Stomp on the brakes.

- Turn the wheel too fast.

You made it to the top of the hill with smooth fluid moves and smaller adjustments. You couldn’t do it coming from the other direction because the turn was too sharp. No room to be fluid in that situation.

At work we like to talk about small incremental changes building towards long-term great results. In fact, we’re so “small change” focused we refuse to consider things R&D, because to us the difference between “small changes over time” and “major development project” is often hard to discern, except in terms of the initial risk taken. (For the record, I think many of the assumptions the author of this article makes are pure fantasy. Not that I have better ones, I just know you can’t pull numbers out of your ass and say “they’re the best possible because I don’t have real ones.”)

Consider your dependencies

At work we like to say “you own your dependencies.” Which is to say what when you build things in a manner that forces you to depend on the actions of others, you have to make sure to build things in a way that you can handle a screw up or change by somebody out of your control.

Driving home in the snow was like that, and is why I won’t go out in my car today in Seattle. Even if I do everything perfectly, I “own” the actions of all the other drivers with no experience and poorly equipped vehicles. Sure, when it’s all over I may be found to be not at fault, but my car is still never going to be the same after the crash, and I did choose to take that risk.

Wait for another day

Maybe the most important lesson. The weather was unpredictable and could change quickly. The difference between “wet surface” and “skating rink” is pretty small. But most of the time we had a pretty good idea of when the hill was going to be a serious mess, and sometimes you just stayed home.

Not much different from the reality at work or anyplace else. Sometimes the best thing to do is wait for a better opportunity. As was the case for teenage me, waiting for a better chance is preferable to “park at the bottom and walk” for adult me.

Don’t volunteer information

To this day, I’m really not sure how much of this dad was aware of. Probably quite a bit more than I gave him credit for at the time. He didn’t ask, I didn’t tell. This works well at work and everywhere else, when talking to officials, crossing borders, etc. Bottom line is there are times to talk about what you’re doing, and times when it’s OK that you learn your lesson quietly and not create unnecessary trouble.